Lenders are robbers of Black housing wealth – stop them My multiracial orbit of friends and colleagues were shocked, angry and embarrassed.

So what are we going to do about it?

Recently on social media, I shared a USA Today story about a Black female homeowner in Indianapolis who suspected the value of her house was grossly undervalued. So, on the third try, she had a white friend stand in for the third appraisal.

The result? Carlette Duffy’s home was valued at $259,000. When she was present, appraisals came in at $100,000 and $125,000.

So, are we being told in 2021 that the satirical Jim Crow-era line, “the white man’s ice is colder” still applies?

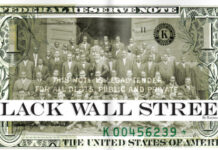

Duffy’s case is not isolated. Housing bias against African Americans is an epidemic. Crippling, too. Wealth has been stolen from Black families for generations, and creative tactics are still in place for the housing industry to commit more felonies.

Take for example “Midwest nice” Minneapolis, ground zero because of the George Floyd slaying. That case resulted in a spotlight being placed on other aspects of Black Minnesota life.

PBS and TPT reported that Blacks in Minneapolis were herded into a particular part of town and were prevented from purchasing houses elsewhere because of restrictive racial covenants that were not lifted until days after Martin Luther King Jr. was killed. Black homes were undervalued because the neighborhoods were starved of services and commercial support.

Want more? Comedian/Hollywood star D.L. Hughley was living large in California, but even he suspected he was being shorted on the value of his house. He persisted and was granted a second opinion.

Hughley was right. The appraiser shorted him $125,000 before the amount was corrected.

Housing discrimination is graphically depicted in “Them,” a 10-episode Amazon Prime series about a middle-class Black family that flees North Carolina for Southern California in the 1950s. They buy a house in Compton, at that time a white suburb. Their neighbors wage a psychological torture campaign against them.

The Black folks should have known their places and settled in Watts, said the whites, and the Black folk in that ’hood said, see, we told you so.

Lead character Henry Emory, husband, World War II veteran and engineer from an HBCU, signed a deed that had a racial covenant, but the white female agent assured him that the words on the paper were unenforceable. Maybe not in court, but definitely on a block with hostile white property owners.

Personally, I have had to play this demoralizing game. Two decades ago, we bought a ranch house in a predominantly white section of Hampton Roads, Va. Our neighbors were cordial and welcoming – and should have been – because our family did add value to the leafy cul-de-sac neighborhood.

When it was time to sell however, we had to move the art we cherished from the walls and mantle: African sculpture, a framed Harper’s Weekly caricature of a slave ball in Charleston and, especially, the framed drawing of a Black man and his woman together in a tug of war, both resolutely pulling the American flag to their side. In a furnished home on display, those items would reflect our Blackness and drive down the true value of our home.

I am infused with pride and self-love, yet I needed to be practical, so those items were hidden from buyers. Yes, the house in Virginia eventually sold for an acceptable price.

Yet anecdotally, examples of homeowner discrimination and marginalization keep cropping up.

“It happens all the time,” said Thomas G., a homeboy from Brooklyn, N.Y., who reunited with me on Facebook after being mutually out of touch for decades.

He’s a pal who made the reverse migration home to the South.

My best friend and godfather to my daughter – an Atlanta bank executive and now a real estate executive – decades ago made the reverse migration south, too.

“Bad paper” he said dryly in 2008, when the Great Recession exposed lenders who steered Black homebuyers to subprime loans that resulted in a trail of defaults and bankruptcies.

As Marvin Gaye famously sang 50 years ago, “makes you wanna holler, throw up both your hands.” But the time for complaining is over. Each time such discrimination comes to light, we must expose it, confront the authorities, get answers and compensation.

Duffy in Indiana shed tears, but she reclaimed her money, too.

Wayne Dawkins is a professor of professional practice at Morgan State University School of Global Journalism and Communication.