Black Wall Street: The Forgotten Women

The neighborhood attacked in the Tulsa Race Massacre was known as a Black intellectual and financial mecca. Women were a little-known part of its success.

By Brentin Mock

Here’s what’s known famously about Greenwood, the early 20th century Black community of Tulsa, and infamously about its destruction: Black businessmen helped build Greenwood into a financial Black mecca that produced an abundance of successful entrepreneurs, some of whom turned into millionaires.

A young Black man, Dick Rowland, accused of accosting a white woman in an elevator, became the impetus for one of the worst race riots in U.S. history. That riot began with a mob of white men from Tulsa and beyond who flocked to the courthouse to lynch Rowland, which led to the assemblage of a counter-mob of Black men who took up arms to defend him.

These are the beginning chapters of what would become known as the Tulsa Race Massacre, which took place 100 years ago this week. From May 31 to June 1, 1921, white people — many of them law enforcement — shot up, bombed and burned down the dozens of Black-owned businesses and hundreds of Black homes that made up Greenwood, killing nearly 300 Black residents and injuring and displacing thousands more.

It’s a story told almost exclusively about, and through, men.

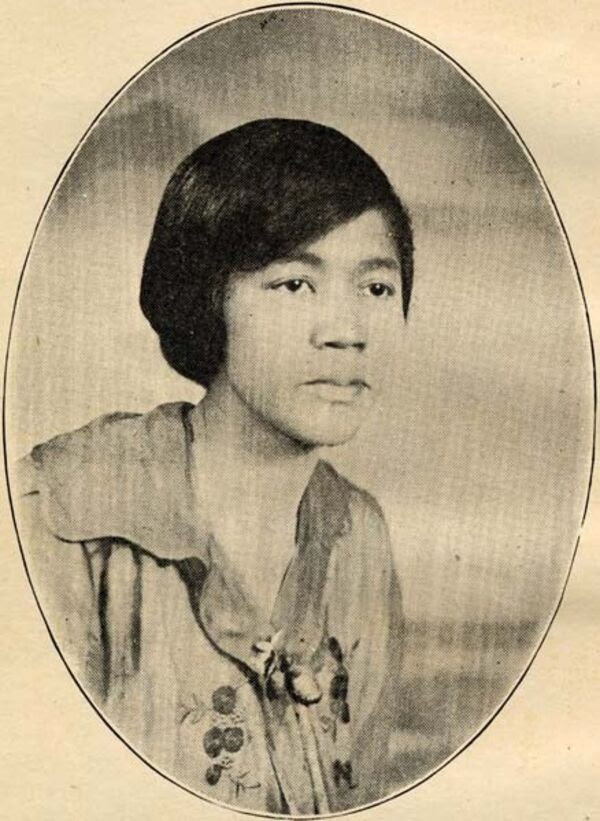

However, we only know many of the lurid details about that massive tragedy because of a Black woman named Mary E. Jones Parrish, who ran a typing school on North Greenwood Street. Her book, Events of the Tulsa Disaster, published in 1922, tells her own story along with eyewitness accounts from dozens of other Black Greenwood survivors. There’s been little known about the Black women of Greenwood who, like Parrish, helped create the neighborhood’s national reputation as a haven of Black intellectual and financial prowess, known popularly as “The Negro’s Wall Street.”

Emerging scholarship on Greenwood is changing that, showing that Black women were as critical to building Greenwood as they were to helping Black people survive the massacre, and rebuild the neighborhood afterward.

“Women tend to play a supporting role in the narrative,” writes Victor Luckerson, an independent journalist, in his blog/newsletter Run it Back. “But who were they? History has been designed to omit large portions of the Black experience, and the issue is compounded for Black women.”

Luckerson has been living in Tulsa for more than a year now conducting research and interviews for his forthcoming book Built From the Fire, which he says will provide a more expansive historical narrative beyond just the massacre. However, he credits Parrish’s book as “the most essential primary text” about what happened during that disaster, even as few others have afforded her this throughout history. In fact, the city of Tulsa worked actively for decades to ensure that the Greenwood disaster story would stay buried in the ashes.

“Like many other women in Greenwood, she’s become a footnote in a story she herself helped establish,” writes Luckerson. “The opportunity to collect the voices of the women of early Greenwood is now lost forever, but modern tools make it much easier to scrape the fragments of the past and at least attempt to paint a fuller picture.”

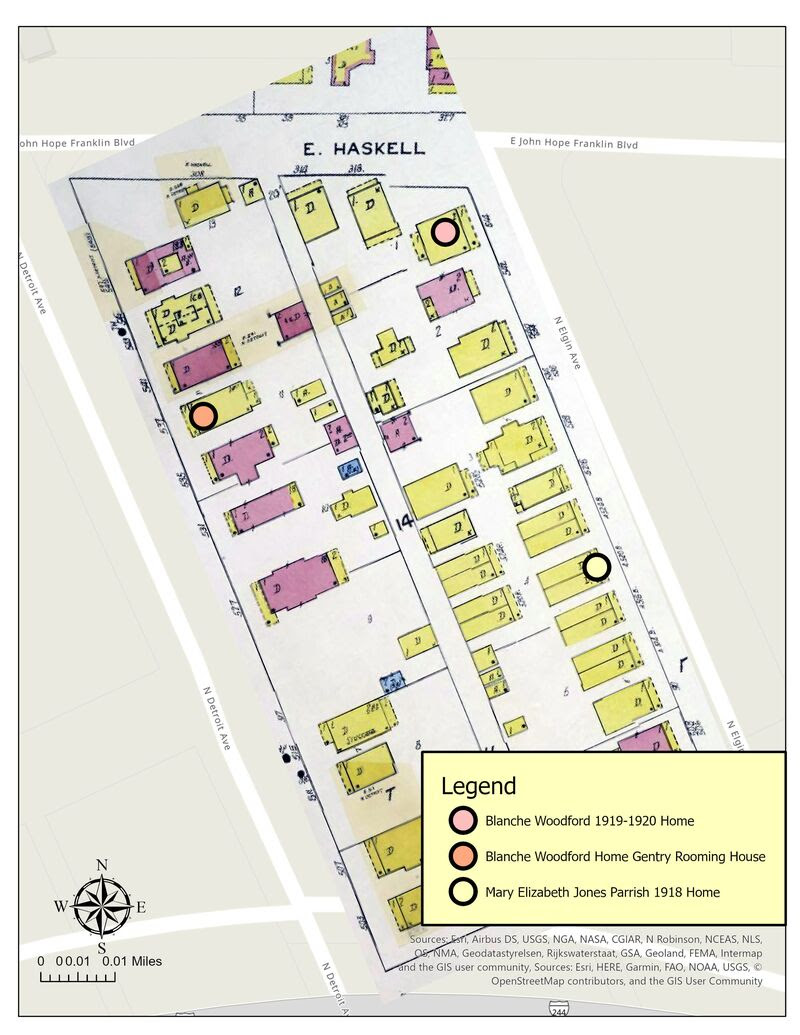

Professor Brandy Thomas Wells, who teaches history at Oklahoma State University, has been working with her students to do exactly that. On May 31, they will launch the “Women of Black Wall Street” website, which features the stories of Black women in Greenwood along with maps of where their businesses and homes were. The website is the culmination of a year-long research project she conducted with her students where they learned how to use digital methods and GIS technology to tell a “multidimensional and intersectional” Greenwood narrative that featured more than just the Black millionaires.

“We were able to have a conversation about Black women’s invisibility,” said Wells. “Sometimes we turn Greenwood into a myth where it’s the only place where Black people were, quote, doing well, and then it becomes the place where every Black person was doing well, and that’s just not true.”

The biographies will be posted on the website over the next few weeks, but the first one up tells the story of Susie Bell, who owned and ran The Bell Cafe and the Busy Bee Cafe, restaurants where Black professionals and church leaders regularly convened and held events. While many women in Greenwood were known primarily through their spouses, Bell apparently was a known quantity within her own right.

“Bell’s name never appeared alongside a man other than brother and business partner, Preston,” reads the profile. “In a world where media was primarily concerned with men’s dealings, it is clear that Bell stole the spotlight.”

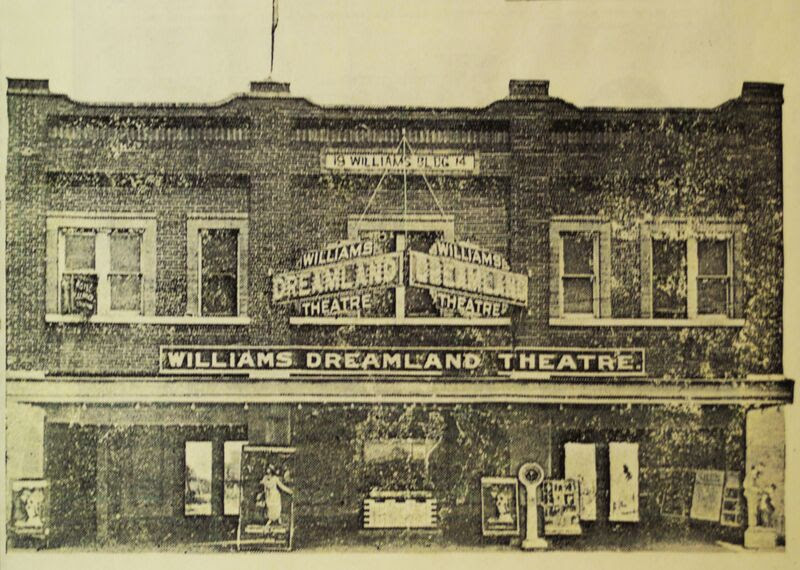

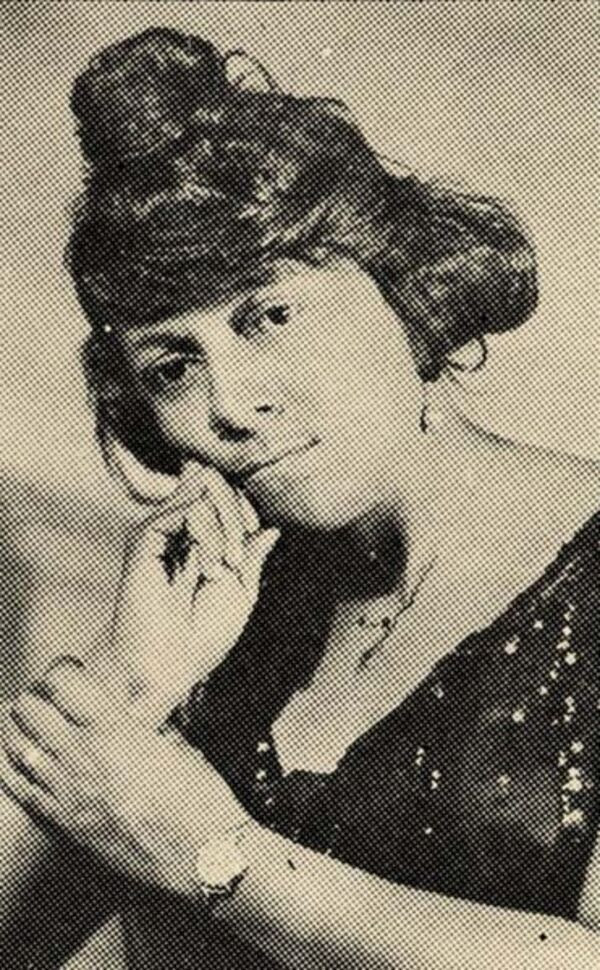

Other prominent Black women of Greenwood include Mme. Geo W. Hunt who owned the Creole Beauty Parlor, which reportedly served Black and white customers; Mabel Little, who also owned a beauty parlor and whose post-massacre rebuilt home is one of the few still standing today as part of the Greenwood Cultural Center; Loula Williams, who at first co-owned the famous Dreamland Theater with her husband John Williams, but eventually became its full owner; Emma Gurley, who with her husband O.W. Gurley basically helped build Greenwood through a cluster of businesses and properties they owned; and Dora Wells, owner of the Wells Garment Factory, who was instrumental in helping rebuild Greenwood — “the first person to erect a frame building in the much coveted district,” according to Parrish’s book.

Wells was able to marshal clothing, money and other resources to Tulsa’s Black refugee families due to her national connections as a member of the Elks and other racial uplift and church-based associations. Before the massacre, Greenwood was what we would call today a “viral hit” — known nationally in a pre-TV and pre-internet world due to Black Tulsans’ connections to nationwide networks and organizations.

“It’s interesting to think about Black Tulsa being connected with political and social developments happening all over the country, large national organizations that were founded for Black unity, cooperation and Black excellence,” said Professor Wells — not to be confused with Dora Wells. “By focusing on these organizations, we move beyond labor. We always want to talk about people in Greenwood working and what they have in terms of economics, but they were tied in politically to Black people in other places. And then we see Greenwood massacre as a part of a longer history of racist violence against Black people.”

Parrish, the author, was herself well-connected outside of Tulsa. In fact, she had only arrived in Tulsa from Rochester, New York, less than two years before the massacre, lured there by the opportunity to participate in the development of what was shaping up to be a Black financial mecca.

“The Tulsa colored people, in every sense of the word, were building a modern, up-to-date business city,” she wrote in the preamble of her book.

Parrish begins the Events of the Tulsa Disaster with a polemic against mob violence, which she notes had no longer been the exclusive province of the Deep South, and a warning to white politicians that if they didn’t stop it, that it would eventually visit violence upon their own people (a prophecy that came to visible display, for instance, 100 years later during the Jan. 6 ransacking of the U.S. Capitol).

Documenting the harsh details of her displacement from her home with her daughter during the disaster, and their search for sanctuary outside of Tulsa in the aftermath, Parrish writes that family and friends across the country implored her to leave permanently. She refused, telling them all that she wanted to help rebuild Greenwood. She was hired by an organization called the State Inter-Racial Commission to interview survivors for a report on what transpired. That reporting is how we know that the massacre was not instigated by Black Greenwood, as was originally reported by the Tulsa media of the day. It’s also how we know that Greenwood wasn’t just a playground for the best and brightest and wealthiest of Black America.

“Greenwood was a dynamic place and we have to teach a history of Greenwood that is not flattened,” said Wells. “Greenwood was able to exist, in part, because it was land that white people did not want. It was downhill. Sewage ran in the streets. The city didn’t pick up trash in Greenwood. They didn’t have streetlights. Yes, there were some pristine parts of Greenwood. Absolutely. Celebrate that. But there were also parts of Greenwood where people really struggled to live. And for me as a Black woman, in the United States, I will argue every day that there’s value in those lives too. It’s about all of those people whose names we don’t celebrate.”