Public Restrooms – Where did all the Public Restrooms go?

Surviving a pandemic has a way of forcing people to focus on the basics: health, food, shelter, the need for human connection — and going to the bathroom.

This became evident during the Great Toilet Paper Shortage of 2020, when panic buyers emptied store shelves in the first weeks of U.S. stay-home orders. As Covid closures continued, the pandemic revealed a different toilet-related problem that predated the novel coronavirus: a dire lack of public restrooms. Though facilities in bars and retail establishments are often thought of as “public,” widespread shutdowns served as a stark reminder that they’re really not — and that few genuinely public bathrooms remain in American cities.

That reality was underscored as the pandemic dragged on. Infection fears led cities to padlock the few public restrooms that were available. Stories emerged about Amazon and Uber drivers resorting to peeing in bottles, while unhoused individuals relied on adult diapers or five-gallon buckets filled with kitty litter. Public urination complaints spiked in cities like New York and Washington, D.C., especially when crowds flooded the streets in the summer of 2020 to protest the murder of George Floyd.

“The state of public restrooms in the U.S. is pretty deplorable, with certain exceptions,” says Steven Soifer, president and co-founder of the American Restroom Association. “Public restrooms are a half-assed job. This is a public health concern, especially with Covid. It’s been a mess.”

The lack of public restrooms in the U.S. hasn’t gone unnoticed. In 2011, a United Nations-appointed special rapporteur who was sent to the U.S. to assess the “human right of clean drinking water and sanitation” was shocked by the lack of public toilets in one of the richest economies in the world. A full accounting of truly public facilities is elusive, says Soifer, but government-funded options are exceedingly rare in the U.S., compared to Europe and Asia; privately owned restrooms in cafes and fast-food outlets are the most common alternatives. According to a “Public Toilet Index” released in August 2021 by the U.K. bathroom supply company QS Supplies and the online toilet-finding tool PeePlace, the U.S. has only eight toilets per 100,000 people overall — tied with Botswana. (Iceland leads their ranking, with 56 per 100,000 residents.)

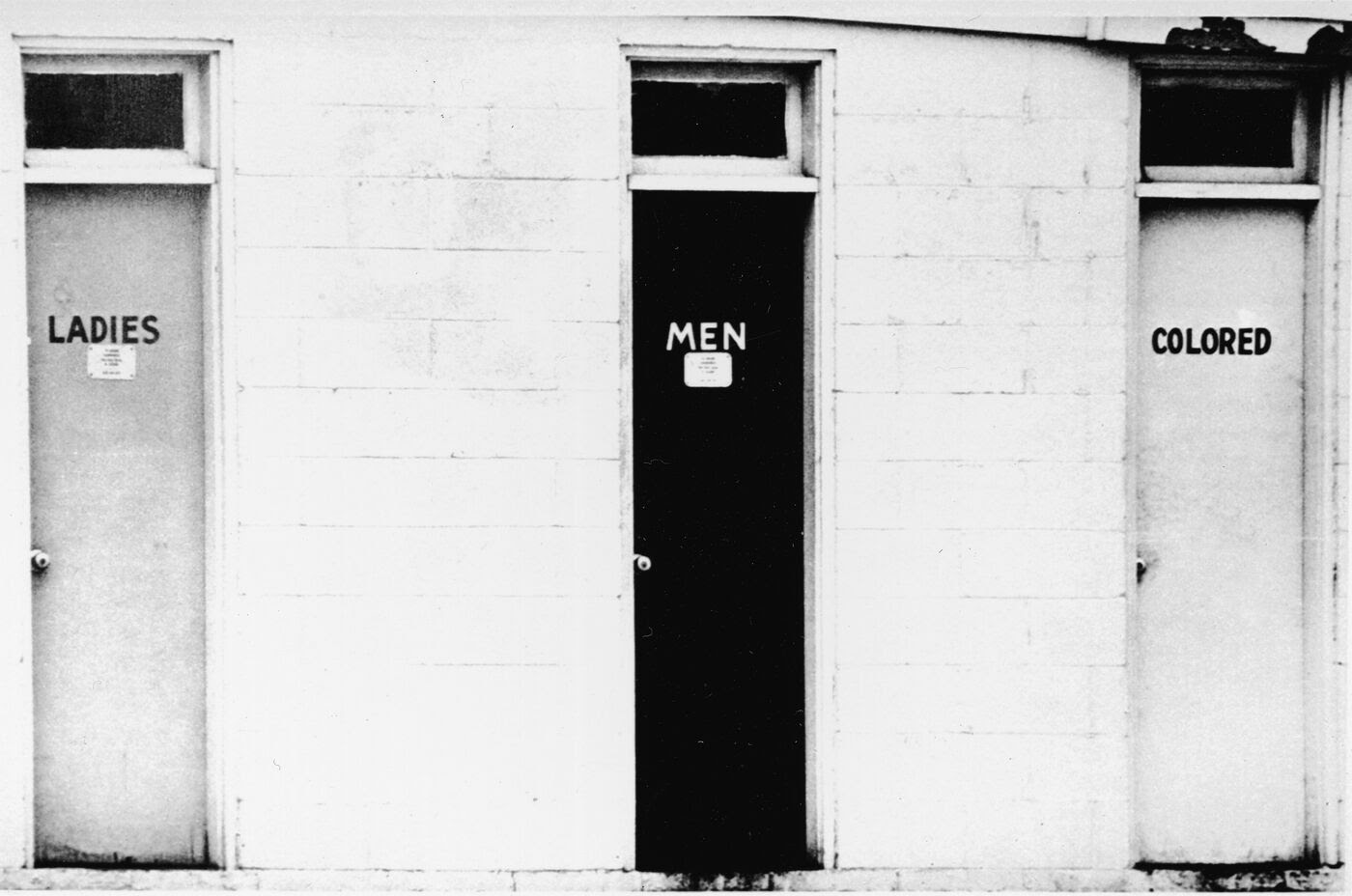

The presence or absence of restrooms in public spaces has long been an indication of a particular group’s place in society, says Laura Norén, a postdoctoral associate at New York University and co-editor of Toilet: The Public Restroom and the Politics of Sharing. From women to people of color to those with disabilities, vulnerable communities have struggled to have this most fundamental of needs accommodated. Most recently, transgender individuals have found themselves targeted in bathroom-backlash debates.

“It’s basically the same script that just plays over and over and over again — and these social tensions often meet in the bathroom,” Norén says. “Who gets access to the bathroom really could be summarized as who should have access to public space and public discourse. Somehow, that crystallizes around the bathroom, because people’s fears are the highest in the bathroom.”

So how did Americans end up with so few places to go? Understanding this requires a look back at the societal and sanitary conditions behind public restrooms in American cities — and the moral panics that propelled both their creation and downfall.

‘Separate spheres’ and shared privies

In the Victorian era, the “separate spheres” ideology — that a woman’s place was in the home, while men had the run of everything else — dictated life for members of the middle- and upper-classes. This was further reinforced by the fact that women in that demographic had few options for relieving themselves while out in public that provided an acceptable level of privacy and comfort. City-dwellers crammed into tenements, meanwhile, considered themselves fortunate if they lived in a building with on-site outdoor privies shared with their fellow residents.

That started to change in the second half of the 19th century. City sewer and public water systems brought improvements in sanitation, and the link between human waste and the spread of diseases like cholera and typhoid — initially thought to be caused by “miasmas,” or bad smells or vapors — gained wider acceptance. In 1865, a group of New York City physicians released a report on public health and hygiene in the growing metropolis, which included recommendations for public urinals that resembled the pissoirs of Paris. The following year, the New York Metropolitan Board of Health began planning what were to be the city’s first two public restrooms, each located in busy theater districts.

Ultimately, only one came to fruition: an above-ground, cast-iron, cupolaed structure at Astor Place and 8th Street that opened in 1869. Plans for this prototype public restroom indicated that it housed both a “women’s compartment” — featuring two stalls and a washbasin — and a “men’s compartment,” with three urinals, two seats, and no stall doors or privacy.

According to an 1897 report by the Mayor’s Committee of New York City, the structure drew close to 1,000 men daily, but no more than 25 women. In addition to not yet being accustomed to the idea of relieving themselves in public (at the center of a busy intersection, no less), the restroom posed other challenges for women, including the lack of space upper-crust ladies required to maneuver their voluminous skirts. Peter Baldwin, a professor of history at the University of Connecticut who has studied the emergence of public restrooms in the U.S., speculates that inhospitable temperatures may have also been a factor.

“It must have been horribly hot in summer, and I imagine the freezing cold cast-iron facilities might not have been appealing to women in winter,” he says.

This pioneering public restroom also didn’t last very long: After deeming its location “in too public a place,” the Department of Public Works tore it down in 1872.

Around the same time, cities like Boston, Providence, and Cincinnati also installed small public urinals for men. But the units could be a tough sell, as nearby businesses resisted. Not only were these public urinals foul-smelling and unsightly, but they still left half the population with nowhere to go.

In the Progressive Era, a washroom wave

It would take the coming of the Progressive Era to bring a major emphasis on hygiene and cleanliness: As housing reformers pushed for improved living conditions in tenement areas, restrooms and bathing facilities began to appear in earnest in U.S. cities.

These were public health measures, rooted in the idea that people of the lower classes — immigrants in particular — were prone to spreading infectious disease that could reach those of higher status. It was also a moral crusade: Many reformers insisted that public amenities helped members of the lower classes avoid drunkenness, violence and promiscuity. In the American Journal of Sociology in 1901, reformer Francis R. Cope, Jr. of Harvard University called tenements “death-breeding, crime-breeding hovels” and made the case that wealthy city residents had a responsibility to address the “tenement-house-reform problem” for the greater good of society.

Progressives found their cause overlapping with the anti-alcohol temperance movement that had emerged earlier in the 19th century. Starting in the mid-1870s, public health and temperance reformers pushed to install water fountains in crowded parts of cities, so that men could quench their thirst without visiting a nearby tavern. (For now, we’ll overlook the public health failure that was the common cup.) A similar campaign for public restrooms soon followed. Strategically positioned toilets meant that men would no longer have to rely on bathrooms in bars — and in turn, wouldn’t be obligated or tempted to grab a shot or beer.

Thanks to a combination of the impact of public health and social reform campaigns and improvements in urban infrastructure, the first years of the 20th century saw a proliferation of public toilets. “There was a big surge of construction [of public restrooms] in the 1900s and 1910s, because there was concern that when Prohibition came in, it was going to close down the go-to public restrooms,” says U Conn’s Baldwin.

The more elaborate examples of these “comfort stations” were sited underground. Following London’s lead, New York City opened its first subterranean restroom in 1897, and Boston’s debuted a year later. Other larger cities — like Cincinnati, Cleveland, Denver, Detroit, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Seattle and Washington, D.C. — followed suit, building their own underground comfort stations in the 1900s and 1910s. Most were designed with high ceilings and covered with gleaming white tile, to instill confidence in their sanitation standards (and counterbalance the discomfort that might arise from descending below street-level for the purpose of relieving yourself).

Privacy, at a price

A final boom in public bathroom construction lasted from roughly 1918 to 1921, a period that coincided with the Great Influenza pandemic and the end of World War I. But then the push for public toilets stalled out.

After the 18th Amendment took effect in January 1920, those who campaigned for public restrooms as a way to keep people out of bars had achieved their goal. And they weren’t the only ones to run out of steam. “The 1910s were still part of the Progressive Era, and there was high prestige for what the government could do,” Baldwin says. “But by the 1920s, there was a sense of exhaustion.”

The often-ornate architectural features of public comfort stations made these facilities costly to build and maintain. Plus, the women who originally campaigned for these spaces had since moved on to a different type of public restroom. Upper- and middle-class white women gradually gained access to hotels, theaters, train stations, and, most notably, department stores. These privately owned establishments offered a far more enticing option — “public” restrooms designed to mimic the design and comforts of home, with lounges full of sofas and vanities for freshening up.

But out of all the amenities this new class of restrooms provided, few had the appeal of their exclusivity. These weren’t pay toilets, per se, but the expectation was that the people using them had purchased tickets to a play or a railway journey, or beverages while socializing in a hotel, or spent the afternoon shopping in a department store. The latter, Baldwin says, were the most accessible to customers of varying classes. So, in an effort to keep well-heeled patrons of high-end retail establishments content, “bargain basements” opened on lower levels — giving less-affluent women a place both to shop and use the facilities without mingling with wealthier clientele.

This line of thinking — a contributing factor to the decline of public restrooms — involved a shift from believing that the government should be responsible for providing bodily privacy, toward what Baldwin calls a consumer model of privacy. “If the individual wants to purchase privacy, you go right ahead,” he says. “You go to that restaurant, and you buy your coffee so you can use the bathroom. But [providing bodily privacy] is not the responsibility of the taxpayers. And that seemed to be America’s choice.”

Nowhere to go

Access to bathrooms is also entangled in deeper inequities. Towns and cities in the Jim Crow-era South boasted fewer public restrooms in general, compared to the Northeast or Midwest, because of the extra costs associated with the “separate but equal” mandate used to legally enforce racial segregation. “In these areas where you had Jim Crow, if you were to build public restrooms, you can’t just have two — you’ve got to have four,” Baldwin says. “If you were going to install public restrooms at all, it was going to cost you twice as much as it would in the North.”

That same reluctance to accommodate all members of the public heralded an era of bathroom neglect.

In the 1930s, New Deal programs like the Works Progress Administration were part of the country’s final effort to increase access to public toilets. But the WPA focused primarily on building utilitarian comfort stations in city, state and national parks instead of urban areas. The WPA also worked alongside the Civil Works Administration to construct a total of 2,911,323 outhouses officially known as “sanitary privies” (unofficially known as “Roosevelt rooms”) on both public and private land in rural areas across 38 states and Puerto Rico between December 1933 and June 1942.

The post-World War II flight to suburbs brought an increased reliance on cars and the the rise of a different kind of public bathroom — the highway rest stop. As the federal interstate system took shape, a network of rest areas sprung up along exits to supply motorists with much-needed toilet facilities and snacks. (Today, these options are also disappearing as state highway departments trim their budgets.) Meanwhile, inside cities, downtown shopping districts declined, limiting access to the most widely used de facto public restrooms. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, most of the genuinely public bathrooms in downtown areas were city-operated pay toilets, where visitors would pay a nominal fee (often a nickel or dime) for use of the facilities, which would go toward keeping them up and running.

In 1970, there were more than 50,000 coin-operated public restrooms in the U.S, according to Pacific Standard. But, for a variety of reasons — including lobbying from feminist organizations and student activists who saw this arrangement as unjust — by 1980, pay toilets in the U.S. were nearly extinct. For the most part, free public restrooms didn’t open up in their place, as the campaigners had hoped.

Fears of crime and vandalism in the 1960s and ’70s sped the mass extinction of many city-run facilities, which had acquired an unsavory reputation as sites of drug use and sexual encounters. By the early 1980s, most of the restrooms located in New York City’s 472 subway stations were locked, and have largely remained inaccessible since. A final blow came in the form of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, prompting the closure of public restrooms across the country for security purposes.

Since then, the American city has largely been a no-go zone.

Visions for the toilets of tomorrow

Progressives of an earlier era managed to improve access to public restrooms. What would it take for modern reformers to mount a toilet comeback?

Consider New York City’s attempt at installing self-cleaning public pay toilets back in 2008. Inspired by the standalone public toilet pods found throughout European cities — though most closely associated with Paris — the New York City version cost a quarter per use, permitted patrons to remain inside for a maximum of 15 minutes, and featured 90 seconds of automated cleaning after each visitor. When the first one hit the streets in January 2008, the New York Times referred to it as “a 25-cent journey to the future.”

But only five of the 20 automatic pay toilets New Yorkers were promised ever were installed. (All are still in use.) As of August 2018, according to Gothamist, the 15 remaining toilets, which the city had already purchased, remain in a Queens warehouse.

Self-cleaning pay toilets have been slow to catch on, says Norén, because require a lot of water and the ability to tap into larger water mains. They also have a footprint roughly four times larger than their non-self-cleaning Parisian counterparts. “Basically, [Americans] are afraid of strangers,” she says. “It was considered beyond the pale that you would install a public toilet that didn’t practically burn itself down and rise from the ashes every time someone used it.”

As with so many other aspects of American life, Covid-19 exposed and exacerbated the American bathroom gap: While the affluent purchased increasingly ornate fixtures for their homes, delivery drivers and other essential workers struggled with ever-more-limited options. In cities with high rates of homelessness, efforts to install temporary hygiene facilities during lockdowns often met resistance from community members and city officials, even as frustrated local businesses locked their restrooms to prevent use from unhoused individuals.

“We have used that to demonize certain classes of people whenever it’s convenient to do so — and it’s almost always convenient to do so,” Norén says. “That’s one of the ways to control who gets to be in public.”

“If you don’t have public bathrooms, what you’re saying is, ‘We do not care about anyone who doesn’t have money.’”

Toilet co-editor Harvey Molotch, an emeritus professor of social and cultural analysis and sociology at New York University, also sees the pandemic as an opportunity to reconsider how public restrooms are built — particular with regards to airflow. Modern heating and ventilation systems and electric lighting made this less of a priority in 20th century public restroom design, which was typically windowless; Molotch hopes to see a reversal of that trend, by adding windows, skylights and other openings.

“Ventilation just makes life better,” he says. “That goes for disease prevention, and of course, the noxious odor. If you increase the ventilation, it ticks off a whole lot of boxes where you have scored an improvement.”

There also needs to be a new approach to restroom “choke points,” Molotch says, especially in high-traffic settings like airports and sports arenas. Current entrances and exits are too small, by design. “In order to contain the smells, the noises, and the physical vision of people coming and going — including maintaining our gender segregation — the entrances and exits are narrow,” he says. “That becomes, especially during Covid, a real liability.”

One option is a layout with a clear separation of functions, featuring a bank of toilet stalls opening up to a common space where sinks are located, he says. Ideally, this would also include increased numbers of sinks and toilets, all with the aim of making moving through the restroom easier. “Fluidity is the alternative to choke points,” he says.

Most importantly, Norén wants to just see more public toilets throughout cities. “We put fire hydrants all over the place for the very rare, but very important emergency when something might light on fire,” she says. “Why can’t we couple up with those, and build some basic toileting infrastructure?”

Soifer, of the American Restroom Association, says that some U.S. cities are leading the charge for public restrooms befitting the 21st century. “Portland has been an exemplar in the last decade, and taken a lot of initiatives to put in user-friendly public restrooms on street corners,” he says. The “Portland Loo” — a single-user toilet pod with a vandal-proof design — was initially designed to meet the needs of their namesake city, but has already been installed in more than 20 other locations across North America, including Denver, Cincinnati, San Antonio and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Soifer also singles out San Diego for adding toilet facilities at the city’s beaches. (Downtown, however, the options are more limited.) In 2019, Washington, D.C., took a step in the right direction when its city council enacted the Public Restrooms Act, which aims to provide public restrooms in underserved parts of the city. So far, two standalone public restrooms are in the works, with others to come (eventually).

As public spaces reopen, Soifer has been trying to gauge whether the pandemic guidelines for increased cleanliness and social distancing have triggered any overall improvements in the condition of U.S. public toilets. So far, he’s found that little has changed. “But at least there’s more talk about it — acknowledgment that it’s a pretty bad situation in a lot of places.”

A case for more bathroom talk

As in other chapters of public health history, this Covid-inspired rethinking of restroom function and design could inspire progress in areas outside of disease prevention. Building more gender-neutral family restrooms, for example, would help make it easier for parents and other caregivers to tend to the needs of their children, regardless of how they identify.

“We have a choice about restrooms,” Molotch says. “Do we do the extreme of closing them off — visually, psychologically, and in discourse — or do we have them opened? A possibility that could come out of all of this is that there’ll be a higher degree of openness, including non-gender-specific restrooms.”

But in order for this to happen, Molotch says that Americans need to first get through some conversations we’ve been avoiding.

“It means that we have to acknowledge human waste,” he says. “Talking about public restrooms means that you have to broach a forbidden subject.”

Ultimately, Baldwin views the current dearth of public restrooms as a social justice issue as well as an infrastructural priority.

“If you don’t have public bathrooms, what you’re saying is, ‘We do not care about anyone who doesn’t have money,’ which I think encapsulates where American politics has been going since 1980,” he says. “I hope that there will be a move toward greater acceptance of public spending and government intervention, because that’s what it’s going to take to deal with the problem.”