The global chip shortage is starting to have major real-world consequences

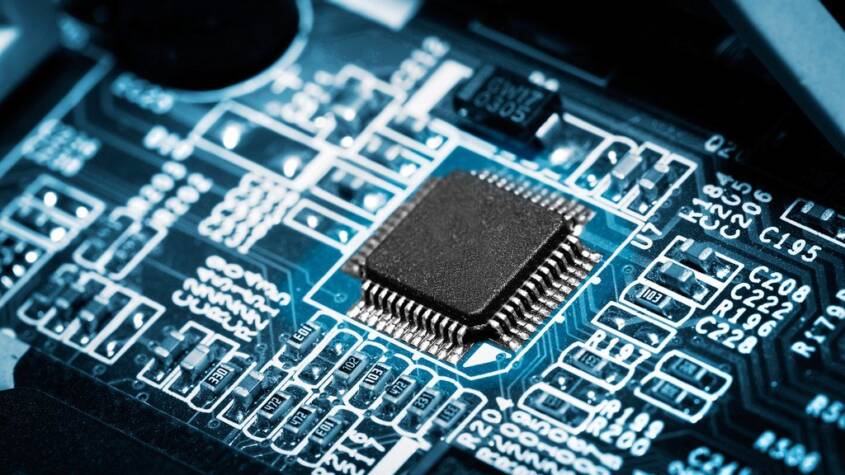

- As technology has advanced, semiconductor chips have spread from computers and cars to toothbrushes and tumble dryers — they now lurk beneath the hood of a surprising number of products.

- But demand for chips is continuing to outstrip supply, and car makers are no longer the only companies feeling the pinch.

- Many companies — particularly those in China who have been hit by sanctions — are boosting their stockpiles of in-demand chips to try to ride out the storm, but that’s making chips even harder to get hold of for other firms.

The severity of the global chip shortage has gone up a notch over the last few weeks and it’s now looking as though millions of people will be impacted.

As technology has advanced, semiconductor chips have spread from computers and cars to toothbrushes and tumble dryers — they now lurk beneath the hood of a surprising number of products.

But demand for chips is continuing to outstrip supply, and car makers are no longer the only companies feeling the pinch.

Alan Priestley, an analyst at Gartner, told CNBC that the average person on the street is bound to be impacted by the chip shortage in one form or another.

“What it will mean is they can’t get something, or prices are slightly higher,” Priestley said during an interview on Thursday.

South Korean tech giant Samsung said last week that the chip shortage is hitting television and appliance production, while LG admitted the shortage is a risk.

“Due to the global semiconductor shortage, we are also experiencing some effects especially around certain set products and display production,” said Ben Suh, head of Samsung’s investor relations, on a call with analysts.

“We are discussing with retailers and major channels about supply plans so that we are able to allocate the components to the products that have more urgency or higher priority in terms of supply.”

Samsung’s co-chief executive and mobile chief, Koh Dong-jin, said at a shareholder meeting in March that there’s a serious imbalance in supply and demand of chips in the IT sector. At the time, the company said it might skip the launch of the next Galaxy Note smartphone.

LG said it is “closely monitoring the situation as no manufacturer can be free of the problem if it gets prolonged,” according to The Financial Times. LG did not immediately respond to a CNBC request for comment.

Everyday appliances at risk

Production of low-margin processors, such as those used to weigh clothes in a washing machine or toast bread in a smart toaster, has also been hit. While most retailers are still able to get their hands on these products at the moment, they may face issues in the months ahead.

Even dog-washing businesses are suffering, according to The Washington Post. CCSI, which makes electronic dog-washing booths in the Illinois village of Garden Prairie, was recently told by its circuit board supplier that the usual chips weren’t available, according to the report.

The business, which did not immediately respond to a CNBC request for comment, was reportedly offered a different chip, but that required the company to adjust its circuit boards, raising costs in the process.

“This particular problem affects all aspects of manufacturing, from little people to big conglomerates,” President Russell Caldwell reportedly said. “Literally we have corn fields around us … there’s not a lot here.”

Many companies — particularly those in China who have been hit by sanctions — are boosting their stockpiles of in-demand chips to try to ride out the storm, but that’s making chips even harder to get hold of for other firms.

Auto industry remains worst hit

The automotive sector, which relies on chips for everything from the computer management of engines to driver assistance systems, is still the hardest hit. Companies like Ford, Volkswagen and Jaguar Land Rover have shut down factories, laid off workers and slashed vehicle production.

Stellantis, the world’s fourth biggest car maker, said on Wednesday that the chip shortage had gotten worse in the last quarter. Richard Palmer, the chief financial officer of the firm that was created through the merger of Fiat Chrysler and Peugeot maker PSA, warned the disruption could last into 2022.

Some carmakers are now leaving out high-end features as a result of the chip shortage, according to a Bloomberg report on Thursday.

Nissan is reportedly leaving navigation systems out of cars that would normally have them, while Ram Trucks has stopped equipping its 1500 pickups with a standard “intelligent” rearview mirror that monitors for blind spots.

“Ram have stopped including (the) option on all Tradesman, Bighorn, Rebel and Laramie models at present due to limited supply of electronic components used in this option,” a Ram spokesperson told CNBC, adding that the company plans to resume offering the option later this year.

Elsewhere, Renault is no longer putting an oversized digital screen behind the steering wheel of certain models. Nissan and Renault did not immediately respond to a CNBC request for comment.

Rental car companies are also feeling the effects as they’re unable to buy the new vehicles they want, according to a Bloomberg report on Tuesday. Hertz and Enterprise, which have traditionally profited from buying new vehicles in bulk and renting them out, have reportedly resorted to buying used cars at auction instead.

“The global microchip shortage has impacted the entire car rental industry’s ability to receive new vehicle orders as quickly as we would like,” a Hertz spokesperson told CNBC.

Hertz said it is “supplementing” its fleet “by purchasing low-mileage, preowned vehicles” from auctions and dealerships.

An Enterprise spokesperson said the global chip shortage “has impacted new vehicle availability and deliveries across the industry at a time when demand is already high.”

Complex issue involving many moving components

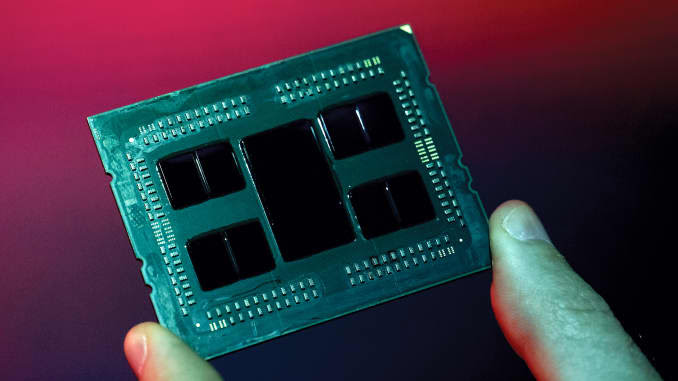

The world’s largest chip manufacturer, TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), said on Sunday that it thinks it will be able to catch up with automotive demand by June.

But Patrick Armstrong, CIO of Plurimi Investment Managers, told CNBC “Street Signs Europe” on Tuesday, that the timeline is highly ambitious.

“If you listen to Ford, BMW, Volkswagen, they all highlighted that there’s bottlenecks in capacity and they can’t get the chips they need to manufacture the new cars,” he said, adding that he thinks it will go on for 18 months.

The chief executive of German chipmaker Infineon said Tuesday that the semiconductor industry is in unchartered territory.

“The current situation, where all verticals are booming, I have never seen before,” Reinhard Ploss told CNBC’s “Street Signs Europe.”

Ploss said it is “very clear it will take time” until supply and demand are rebalanced. “I think two years is too long, but we will definitely see it reaching out to 2022,” he said. “I think additional capacity is going to come … I expect a more balanced situation in the next calendar year.”

Ramping up production takes time. “You can’t suddenly go to a chip vendor and say, ‘give me a million new chips’ if you haven’t got the order in place because there’s a throughput time,” said Priestley, who works in Gartner’s technology and service provider research team. “If I put an order in today, and there’s capacity available, it may take me three months or more to get the chip.”

He added that most consumer products have extended supply chains and “we haven’t started to see the impact” of the chip shortage in some areas. “If Apple builds a new phone today, they may not ship until end of the year,” said Priestley.

Meanwhile, the issue in the automotive industry is being compounded because the car manufacturers don’t use the most advanced — or bleeding edge — chips, according to Priestley.

“They tend to use chips that are made on older manufacturing processes and the chip companies are obviously moving towards using the higher-revenue bleeding edge products, and they’re not investing in your capacity on the older processes,” he said.

Tech sovereignty

Nations are now being forced to think about how they can increase the number of chips they produce. The vast majority of the world’s chips are made in China, while the U.S. is the second biggest producer.

The European Commission, the executive arm of the EU, has said it wants to build up chip manufacturing capacity in Europe as part of an effort to become more self-reliant on what it sees as a critical technology.

Europe currently accounts for less than 10% of global chip production, although that is up from 6% five years ago. It wants to boost that figure to 20% and is exploring investing 20-30 billion euros ($24-36 billion) to make it happen.

U.S. tech giant Intel has offered to help but it reportedly wants 8 billion euros in public subsidies toward building a semiconductor factory in Europe.

Pat Gelsinger, Intel’s CEO, met with two EU commissioners in Brussels including Thierry Breton last Friday after meeting with German ministers the day before.

“What we’re asking from both the U.S. and the European governments is to make it competitive for us to do it here compared to in Asia,” Gelsinger told Politico Europe in an interview, where he was cited saying that he was seeking roughly 8 billion euros in subsidies.

Intel also announced in March that it intends to spend $20 billion on two new chip plants in Arizona.

“It’s going take two or three years before we start to see that,” said Gartner’s Priestley. “But that’s really looking to meet future demand.”