Walter Francis White helped the NAACP document the truth about lynchings in America. The fact that he could pass as caucasian came in very handy.

On a hot September day in 1919, Walter Francis White found himself running for his life. In the two days since he had been in Elaine, Arkansas, White had seen the bodies of dozens of Black men and women strewn across dirt roads. The ones who were lucky enough to still be alive remained hiding in the cotton fields.

White ducked down an alley, then picked up speed along the railroad tracks. Breathless and weary, he reached the station and climbed onto the platform just as the conductor announced the final call for the doors.

As recounted in White’s autobiography, A Man Called White, the conductor gave White an odd look before asking him why he was leaving before the fun began. “There’s a damned yellow nigger down here passing for white,” the conductor explained. “When they get through with him, he won’t pass for white no more!” he cackled.

What the conductor didn’t know was that the last-minute passenger he was talking to was in fact the very man he was talking about. White later wrote in his autobiography, “No matter what the distance, I shall never take as long a train ride as that one seemed to be.” When he finally set foot back in New York, his colleagues at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sighed with great relief.

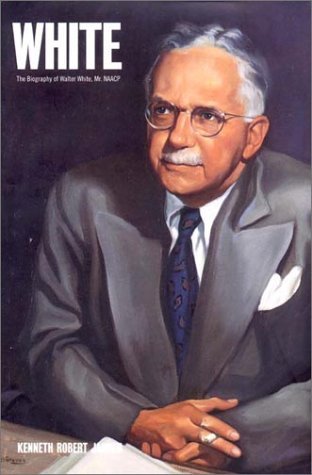

Walter White is one of the most important yet overlooked civil rights leaders of the 20th century. He played a key role in the Harlem Renaissance and led the NAACP to its zenith as its executive secretary. But what makes White stand out is the unusual method he used to achieve racial justice. His biggest secret? He was a biracial man who passed for white in order to help the NAACP investigate some of the greatest racial atrocities in post-Reconstruction America, helping to establish the organization as a veracious force for African-American justice and liberty.

In 1919, White was on assignment in Arkansas investigating the Elaine Massacre: the state-sanctioned murder of dozens of Black sharecroppers under the order of Arkansas Governor Charles Brough. At the time, the Arkansas farming industry was dominated by white landowners, and Black sharecroppers — frustrated by low wages — had formed the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America. That September, the union met in a local church to discuss an upcoming lawsuit against white landowners, but their meeting was interrupted by gunfire from white vigilantes. The sharecroppers returned fire in self-defense. A white security officer was killed, and the town’s deputy sheriff was wounded.

When the news reached the Governor’s Mansion in Little Rock, Brough declared the event an insurrection. He called up 500 Arkansas National Guard soldiers from Camp Pike and instructed them to kill any Black person who refused to surrender immediately. More than 200 African-Americans were murdered and an additional 200 were tortured and imprisoned. A century later, the Elaine Massacre remains the bloodiest occurrence of racial violence in Arkansas history and one of the deadliest in U.S. history as well.

White traveled to Arkansas to advocate for those imprisoned sharecroppers. He planned to meet with the local sheriff and report back to the NAACP. But it was not safe for a Black man to freely roam around Arkansas. So White devised a plan. He obtained fake press credentials through personal contacts, and impersonated a Chicago Daily News reporter, hoping everyone would assume he was white.

But right before his meeting with the sheriff, his plan backfired.

As White recounted in his memoir, while he was walking down the street, he was overtaken by a Black man who whispered, “Mister … I don’t know what you are down here for, but I just heard them talking about you — I mean the white folks — and they say they are going to get you.” With that warning, White started sprinting to the train station and never looked back.

Walter White was born in Atlanta in 1893. His maternal grandmother is believed to have been the illegitimate child of William Henry Harrison, the ninth president of the United States and a slaveholder. White’s father, George, a postman, also had white ancestry. In the book Walter White: The Dilemma of Black Identity in America, author Thomas Dyja notes that while Walter grew up going to white schools, he always knew that he was different than his peers — and so did they. His white classmates threw rocks at him, while Black peers often mocked him for his light complexion. But on September 22, 1906, White would understand that despite the lightness of his skin, he was not white.

A headline splashed across the front page of The Atlanta Evening News — “Bold Negro Kisses White Girl’s Hand” — would initiate the Atlanta Race Riot. The story sparked outrage, and mobs of angry white men began to attack African-American communities. In A Man Called White, White recalls watching a disabled shoe shiner being beaten until he died in a pool of his own blood. “We saw clubs and fists descending to the accompaniment of savage shouting and cursing,” White wrote. “A voice cried [out] ‘there goes another nigger!’”

White’s father, George, purchased a rifle, and as the mob neared the Whites’ home, he and his son positioned themselves at the parlor windows. George ordered Walter “not to shoot until the first white man stepped on the lawn, and once that man did, not to miss.”

“In that instant, there opened up within me a great awareness,” Walter White wrote. “I knew then who I was. I was a Negro, a human being with an invisible pigmentation which marked me a person to be hunted, hanged, abused, discriminated against, kept in poverty and ignorance in order that those whose skin was white would have readily at hand a proof of their superiority. … Yet as a boy there in the darkness amid the tightening fright, I knew the inexplicable thing — that my skin was as white as the skin of those who were coming at me.”

White never fired his gun that night. Just as the mob approached the lawn and the young man took aim, a salvo of gunshots thundered from a brick building next door. A group of the White family’s friends had staked out a position to protect the popular postman’s family, and White was saved from pulling the trigger — as well as the fate that likely would have befallen him had he fired.

After graduating from Atlanta University in 1916 and working as an insurance salesman, White caught wind of the Atlanta school board’s decision to close the only Black public high school in the city. He decided to establish a local chapter of the NAACP in Atlanta to fight it. When NAACP Field Secretary James Weldon Johnson came to Atlanta, he was so taken with White that he hired him to be his assistant at the New York headquarters.

In February 1918, word reached the NAACP that a mob had brutally tortured, shot and lynched a Black sharecropper named Jim McIlherron in Estill Springs, Tennessee. NAACP leaders met and discussed sending a protest letter to Tennessee Governor Thomas Rye, but they worried that a letter alone would not gain the attention that these incidents warranted. During the meeting, White made a decision that would launch and define his career: He sought permission to go undercover and make a firsthand investigation.

NAACP Executive Secretary John R. Shillady shut down the notion immediately. What would happen to White should Southerners discover that he was biracial and impersonating a white man to investigate on the behalf of the NAACP? White persisted, and eventually, Shillady relented. By the next day, the upstart activist was setting out on a mission that neither White nor the NAACP had ever previously even contemplated. White went undercover.

In Walter White: The Dilemma of Black Identity in America, Thomas Dyja describes how White assumed the identity of a land buyer when he stepped into Estill Springs’ center of activity: the town’s local general store. White had no intention of asking direct questions about the lynching, but before he could even approach the topic, it came to him. Members of the lynch mob were gathered around a fire crackling in the store’s stove, boasting about the details of the lynching. White, seated unassumingly near the men, got the full, gory details, right down to the moment when McIlherron was doused with coal fluid and prodded with a hot iron for 30 minutes until he died.

White would encounter many more difficult moments in this new line of work, as he gained an up close look at the casual callousness behind these vicious crimes. Once, while investigating a lynching in Georgia, he ran into the leader of the lynch mob while shopping in a general store. The mob leader, unaware of who White really was, recounted the whole event, chuckling and slapping his thigh throughout the entire story and declaring the lynching to be “the best show, Mister, I ever did see.” Throughout the conversation, White could barely contain his nausea.

White’s undercover investigations continued, providing valuable details to the NAACP in the battle to end lynching, which affected nearly every corner of the United States, but was most prevalent in the Deep South states where White traveled. (The Equal Justice Initiative’s 2015 report on Lynching in America revealed that more than 4,000 African-Americans were lynched in 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950.) The NAACP published White’s reports and shared them with media outlets, including The Nation, where White published his seminal account of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. White summed up that event as such: “A hysterical white girl related that a nineteen-year-old colored boy attempted to assault her in the public elevator of a public office building of a thriving town of 100,000 in open daylight. Without pausing to find whether or not the story was true … a mob of 100-per-cent Americans set forth on a wild rampage that cost the lives of … between 150 and 200 colored men, women and children; the destruction by fire of $1,500,000 worth of property … and everlasting damage to the reputation of the city of Tulsa …”

“How much longer will America allow these pogroms to continue unchecked?” White asked in his article. “There is a lesson in the Tulsa affair for every American who fatuously believes that Negroes will always be the meek and submissive creatures that circumstances have forced them to be during the past three hundred years.”

At the time of this writing, the City of Tulsa is set commemorate the 100th anniversary of the massacre in May 2021, and it has commissioned the Oklahoma Archeological Survey to dig up a mass grave that many suspect contains the remains of dozens of Black people killed in the massacre.

White worked his way up from investigator to assistant national secretary to eventually leading the NAACP, serving as its executive secretary from 1929 to 1955, working on many prominent legal cases. Unfortunately, White didn’t get to fully realize his vision. He died 10 years before the 1965 Civil Rights Act, and America today is still struggling to execute the vision of racial equality that White dreamt of. But in 2018, two prominent African-American senators stood on the podium of the Senate floor to introduce a federal anti-lynching bill, which would mark a sort of culmination of White’s work.

Senators Kamala Harris and Cory Booker’s Justice for Victims of Lynching Act seeks to classify any bodily harm on the basis of racial discrimination as a federal hate crime. “With this bill,” said Senator Harris, “we finally have a chance to speak the truth about our past and make clear that these hateful acts will never happen again.” The Justice for Victims of Lynching Act passed the Senate unanimously. On February 26, 2020, the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, a revised version of the Justice for Victims of Lynching Act, passed the House of Representatives, by a vote of 410–4. Because of the minor difference between the bill that passed the House and the one that passed the Senate in 2019, the bill must once more be passed by the U.S. Senate before it can go to the president for his signature and become law.

Walter Francis White’s work on anti-racism and civil rights propels our current conversation about race in America forward. He was born into an ancestry that could not fully call itself white or Black, but he fully embraced his African-American heritage. And instead of taking advantage of the privilege that came with his mixed race, he used it to unearth significant truths about Black lives in the darkness before civil rights became a rallying cry.

Following his death, the Amsterdam News wrote that White’s “cocky aggressiveness stayed with him as long as he lived — as did his boyhood vanity. But it was these very qualities that helped to make him the best lobbyist our race has ever produced.”