As protests against police brutality and white supremacy swarm city streets across the country, Americans are relearning the vocabulary of resistance that led to the Civil Rights Act and the end of the Vietnam War — not to mention women’s suffrage and laws against children working in factories. Will widespread social gains be won from the latest mass uprisings?

Belief in Martin Luther King Jr.’s statement that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice” implies that a society won’t endlessly tolerate violence toward its citizens. Already, movements to partially defund police departments and transfer funding to social workers, mental health and addiction resources have won victories in major U.S. cities and, to a smaller extent, in Burlington. And yet, the struggle against systemic injustice is far from over.

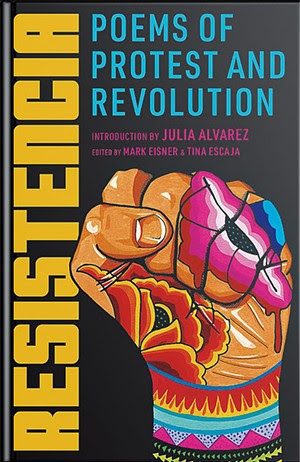

How fitting, then, that a poetic manual for resistance has arrived. Resistencia: Poems of Protest and Revolution is a bilingual anthology of poets representing every Latin American country, including those in the Caribbean. Such a diverse selection resists an easy description, yet the poems here are united against imperialism, oppression, greed and violence. From 20th-century icons to rousing new voices, the poets within Resistencia‘s pages go beyond the American poetic tradition of “bearing witness” to actively participating in the fight for justice, in some cases even living and dying as freedom fighters.

Coeditors Mark Eisner, a writer, translator, and documentary filmmaker, and Tina Escaja, a University of Vermont professor of Spanish, have assembled an all-star team of translators, including Saint Michael’s College distinguished scholar-in-residence Kristin Dykstra (winner of the 2020 PEN Award for Poetry in Translation), former U.S. poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, and Jack Hirschman (famously the Doors front man Jim Morrison’s professor at University of California, Los Angeles, until he was fired for encouraging his students to evade the draft).

In her moving introduction to the anthology, Vermont novelist and Middlebury College writer-in-residence emerita Julia Alvarez notes its radical inclusiveness: In addition to Spanish, Resistencia includes poems originally composed in Maya Kaqchikel (Guatemala), Kreyòl (Haiti), Quechuan (Peru), Miskito (Nicaragua), Mapudungun (Chile), French (Martinique) and Portuguese (Brazil).

Alvarez eloquently sums up the sacrifices some of these authors have made in their fight for justice, which go far beyond the literary: “On one read-through I marked the margins of the index with a small cross for every writer who had been murdered, tortured, exiled, or had succumbed to despair and suicide. The page looked like a cemetery. But turn to the pages themselves, and the poets are resurrected, their voices defiant, alive, presente!”

Editing as an act of resurrection is an apt way to describe the publication of this volume, though some of the contributors are still living, such as Nicaraguan feminist and Sandinista Gioconda Belli. Her instructional poem “Huelga” (“Strike”) feels especially relevant, as an academic strike in the U.S. fails to gain steam. The final stanza reads, “A strike where it is forbidden to breathe / where silence is born / so you can hear the footsteps / of the tyrant as he walks away.”

Readers may recognize a handful of names in Resistencia (Pablo Neruda, Aimé Césaire), but most will likely be unfamiliar. In addition to lauded literary heroes of their respective countries, some contributors are young poets breaking new ground, such as Guatemalan writer, anarchist and feminist rapper Rebeca Lane. (Her translator, Carolina de Robertis, recommends watching her YouTube videos while reading “Poesía venenosa” (“Poisonous Poetry”).

The richness of Latin American poetry is abundantly evident in Resistencia — there could be similar anthologies for every country represented. At 238 pages, it isn’t an exhaustive encyclopedia meant to adorn coffee tables but a book you could shove into your back pocket on the way to a protest. Many lines, such as Roque Dalton’s “Acta” (“Act”) are meant to be read through a megaphone: “In the name of those who have nothing but / hunger exploitation disease / a thirst for justice and water / persecution and condemnations / loneliness abandonment oppression and death / I accuse private property / of depriving us of everything.”

Escaja knows a thing or two about resistance, as well as breaking new ground: She’s the founder of Destructivismo, a movement initiated at the grave of Chilean poet Vincente Huidobro. Her 2016 Manual destructivista declares, “the Destructivist destroys / poetry in its censored shapes / obsolete complicities / canonical restrictions / demystifies it, dismembers it, bites it, tears it / turns it to toilet paper / to origami” (translated by Dykstra). Escaja is widely known in the exciting terrain of hypertext and digital poetry; her experimental work encompasses everything from poetry robots built at Burlington maker space Generator to outdoor performances using sheep with words painted on them.

Escaja and Eisner’s anthology is also something of a poetic history lesson: The oppression that the book’s writers cite was often a result of U.S. foreign policy, such as the Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored coups in Chile and Guatemala. The extent of the devastation wreaked by the CIA becomes less abstract, more personal in the contributors’ notes. Raúl Zurita, for example, wrote that he was detained on the first day of Pinochet’s coup and tortured aboard a crowded prison ship for six weeks.

Of significance is how Resistencia broadens the word “America,” pluralizing it as “the Americas.” After all, the United States isn’t the only nation in the hemisphere. If it’s easy to forget that there is another South beyond our own, Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti provides a reminder in “El sur también existe” (“The South Also Exists”), which Eisner translates as:

With its French horn and its Swedish academy

its American sauce and its English wrenches

with all its missiles and its encyclopedias

its intergalactic war and its opulent brutality

with all its laurels it is the north that commands

but way down here close to the roots

is where memory omits no memories

and there are those who are ready to resurrect themselves

and there are those who are ready to go out of their way

and so together they achieve

what was an impossibility that the whole world might know

that the south also exists.

Bilingual editions, especially of poetry, are immensely rewarding for bilingual speakers. Translation can’t re-create a poem without changing it slightly, so examining those differences is part of the fun. Seeing the original and its English interpretation on facing pages has a similar effect as contrapuntal poetry — that is, a poem written with two distinct halves on either side of the page, which can be read three different ways: left, right, and then as one.

Even readers with just a year of high school Spanish can experience this sensation. For example, Eisner renders Benedetti’s line, “pero aquí abajo abajo” as “but way down here.” This translation communicates the essence of the words in a readable way but loses some of the poetic wordplay of the original: It’s easy to see that “abajo abajo” refers to what’s underneath the underneath.