The Swastika’s History

The Swastika’s HistoryHeinrich Schliemann discovered the archaeological site of Troy, but his discovery also boosted the visibility of swastikas. Illustration from clu / Getty Images.

When archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann traveled to Ithaca, Greece in 1868, one goal was foremost in his mind: discovering the ancient city of Troy using Homer’s Iliad. The epic poem was widely believed to be no more than a myth, but Schliemann was convinced otherwise. For him, it was a map to the hidden location of ancient cities.

Over the next several years the German businessman, who made his fortune in trading raw materials for ammunition production, tramped around the Mediterranean. Schliemann took Homer’s advice on everything from local customs to treating physical maladies. Trained at the Sorbonne, he used Homer’s verses to identify what he thought were the epic’s real-world locations. “One of his greatest strengths is that he had a genuine historical interest. What he wanted was to uncover the Homeric world, to know whether it existed, whether the Trojan war happened,” writes classics scholar D.F. Easton. “But here also is a weakness. He was not very good at separating fact from interpretation.”

It wasn’t until 1871 that Schliemann achieved his dream. The discovery catapulted him to fame, and with his fame came a burst of interest in all that he uncovered. The intrepid archaeologist found his Homeric city, but he also found something else: the swastika, a symbol that would be manipulated to shape world history.

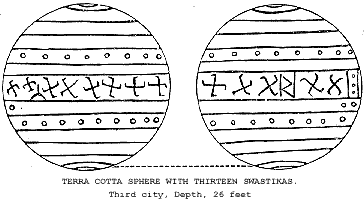

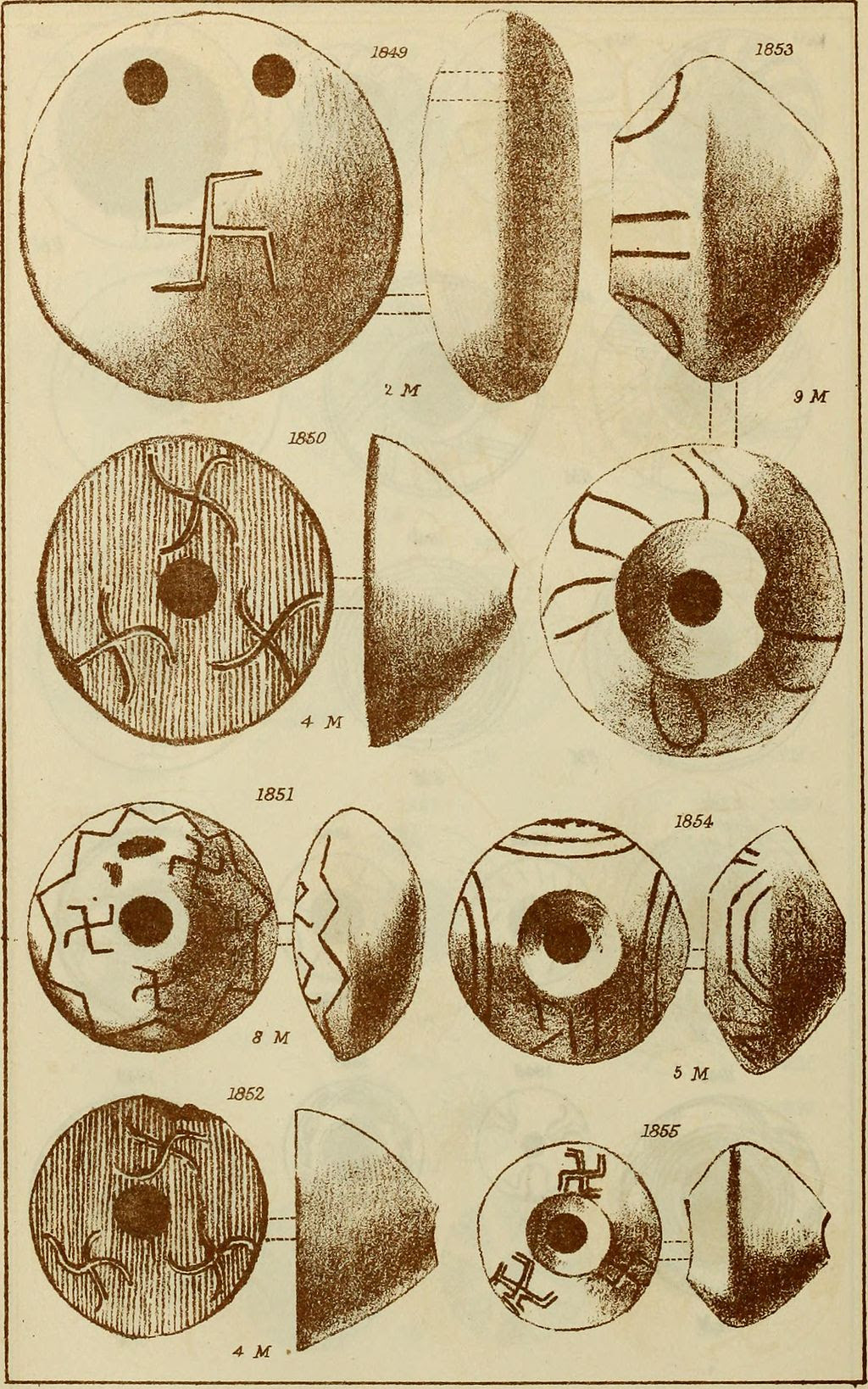

Schliemann found his epic city—and the swastika—on the Aegean cost of Turkey. There, he continued the excavations started by British archaeologist Frank Calvert at a site known as Hisarlik mound. Schliemann’s methods were brutal—he used crowbars and battering rams to excavate—but effective. He quickly realized the site held seven different layers from societies going back thousands of years. Schliemann had found Troy—and the remains of civilizations coming before and after it. And on shards of pottery and sculpture throughout the layers, he found at least 1,800 variations on the same symbol: spindle-whorls, or swastikas.

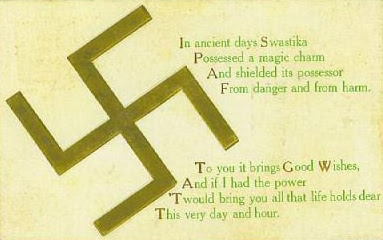

He would go on to see the swastika everywhere, from Tibet to Paraguay to the Gold Coast of Africa. And as Schliemann’s exploits grew more famous, and archaeological discoveries became a way of creating a narrative of national identity, the swastika grew more prominent. It exploded in popularity as a symbol of good fortune, appearing on Coca-Cola products, Boy Scouts’ and Girls’ Club materials and even American military uniforms, reports the BBC. But as it rose to fame, the swastika became tied into a much more volatile movement: a wave of nationalism spreading across Germany.

“The antiquities unearthed by Dr. Schliemann at Troy acquire for us a double interest,” wrote British linguist Archibald Sayce in 1896. “They carry us back to the later stone ages of the Aryan race.”

Terracotta balls from Schliemann’s archaeological digs at Troy bearing swastikas. Photo from Heinrich Schliemann / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Initially, “Aryan” was a term used to delineate the Indo-European language group, not a racial classification. Scholars in the burgeoning field of linguistics had noticed similarities among the German, Romance and Sanskrit languages. The rising interest in eugenics and racial hygiene, however, led some to corrupt Aryan into a descriptor for an ancient, master racial identity with a clear throughline to contemporary Germany. As the Washington Post reported in a story about the rise of Nazism several years before the start of World War II, “[Aryanism]… was an intellectual dispute between bewhiskered scholars as to the existence of a pure and undefiled Aryan race at one stage of the earth’s history.” In the 19th century, French aristocrat Arthur de Gobineau and others made the connection between the mythical Aryans and the Germans, who were the superior descendants of the early people, now destined to lead the world towards greater advancement by conquering their neighbors.

Schliemann found numerous examples of the swastika motif on artifacts from his digs at Troy.Photo by Heinrich Schliemann / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

The findings of Schliemann’s dig in Turkey, then, suddenly had a deeper, ideological meaning. For the nationalists, the “purely Aryan symbol” Schliemann uncovered was no longer an archaeological mystery—it was a stand-in for their superiority. German nationalist groups like the Reichshammerbund (a 1912 anti-Semitic group) and the Bavarian Freikorps (paramilitarists who wanted to overthrow the Weimar Republic in Germany) used the swastika to reflect their “newly discovered” identity as the master race. It didn’t matter that it traditionally meant good fortune, or that it was found everywhere from monuments to the Greek goddess Artemis to representations of Brahma and Buddha and at Native American sites, or that no one was truly certain of its origins.

“When Heinrich Schliemann discovered swastika-like decorations on pottery fragments in all archaeological levels at Troy, it was seen as evidence for a racial continuity and proof that the inhabitants of the site had been Aryan all along,” writes anthropologist Gwendolyn Leick. “The link between the swastika and Indo-European origin, once forged was impossible to discard. It allowed the projection of nationalist feelings and associations onto a universal symbol, which hence served as a distinguishing boundary marker between non-Aryan, or rather non-German, and German identity.”

A postcard mailed from Rochester, New York in June 1910. Photo from Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

As the swastika became more and more intertwined with German nationalism, Adolf Hitler’s influence grew—and he adopted the hooked cross as the Nazi party symbol in 1920. “He was attracted to it because it was already being used in other nationalist, racialist groups,” says Steven Heller, author of The Swastika: Symbol Beyond Redemption? and Iron Fists: Branding the 20th-Century Totalitarian State. “I think he also understood instinctually that there had to be a symbol as powerful as the hammer and sickle, which was their nearest enemy.”

To further enshrine the swastika as a symbol of Nazi power, Joseph Goebbels (Hitler’s minister of propaganda) issued a decree on May 19, 1933 that prevented unauthorized commercial use of the hooked cross. The symbol also featured prominently Leni Riefenstahl’s propagandist film Triumph of the Will, writes historian Malcolm Quinn. “When Hitler is absent… his place is taken by the swastika, which, like the image of the Führer, becomes a switching station for personal and national identities.” The symbol was on uniforms, flags and even as a marching formation at rallies.

Efforts to ban the display of the swastika and other Nazi iconography in the post-war years—including current German criminal laws that prohibit the public use of the swastika and the Nazi salute—seem to have only further enshrined the evil regime it was co-opted by. Today the symbol remains a weapon of white supremacist groups around the world. In recent months, its prevalence has spiked around the U.S., with swastikas appearing around New York City, Portland, Pennsylvania, California and elsewhere. It seems the harder authority figures attempt to quash it out, the greater its power to intimidate. For Heller, this is an intractable problem.

“I think you can’t win,” Heller says. “Either you try to extinguish it, and if that’s the case you’ve got to brainwash an awful lot of people, or you let it continue, and it will brainwash a lot of people. As long as it captures people’s imaginations, as long as it represents evil, as long as that symbol retains its charge, it’s going to be very hard to cleanse it.”

Lorraine Boissoneault is a contributing writer to SmithsonianMag.com covering history and archaeology. She has previously written for The Atlantic, Salon, Nautilus and others. She is also the author of “The Last Voyageurs: Retracing La Salle’s Journey Across Americ