Herschel Walker, Reject Media Claims of ‘Racial Divide’ in Rural Georgia

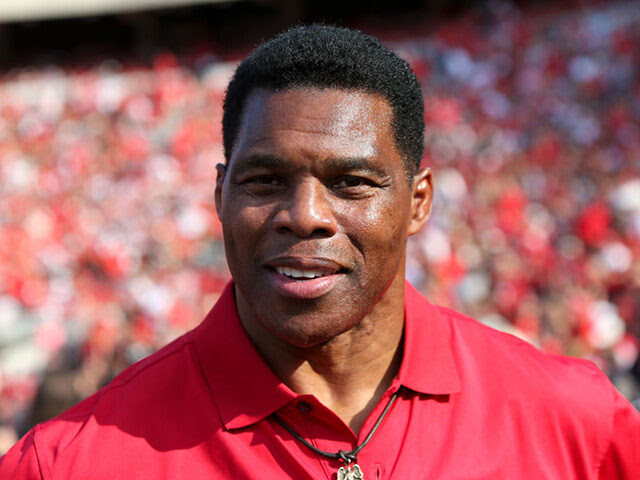

85  Brett Davis/Getty Images

Brett Davis/Getty Images

19 Oct 20221,052

WRIGHTSVILLE, Georgia — Those who knew Herschel Walker before he gained national fame and launched a bid for U.S. Senate are standing up for him after mainstream media attempted to tie the beloved football legend to a “racial divide” in their small town.

A number of residents of Johnson County, a rural county near central Georgia with a population of less than 10,000, spoke highly of Walker in interviews this month with Breitbart News.

They took issue with a recent New York Times report that zeroed in on race in Wrightsville, the county seat of Johnson where Walker was raised.

The report charged that Walker had been ostracized by Wrightsville’s black community because of Walker’s decision to steer clear of tense protests against racism that took place in the area four decades ago.

Joseph Sumner, a local attorney, viewed the Times report as “an attack on rural Georgia,” he said in the driveway of his modest home, which was surrounded by acres of farmland and cottonfields.

“Growing up in rural Georgia, knowing people from all across the socioeconomic strata, I mean, we have a lot of poverty here. You know so many of these people that, they struggle. There’s no jobs here. I felt like there was an arrogance in that you would have a reporter from the New York Times that would come down here to do what I would say was kind of a hit piece, and the people here, and the problems that we’ve had here have been going on for years,” Sumner said. “The truth is they don’t care about these people. … They want to write about their virtues, but they don’t care about the poverty. They don’t care about the drugs.”

Sumner, whose father was a drugstore pharmacist in Wrightsville, has known of the Walkers his whole life and encounters Walker’s family members in and around town frequently.

Walker’s mother, as well as his father when he was alive, are “just a portrait of good, decent, hardworking people” who raised their seven children “to be exceptional,” Sumner said.

“Those comments about [Walker] forgetting where he came from, I completely disagree with that,” he said.

The Times had quoted a former coach of Walker’s saying Walker “forgot where he came from” and that he “is not part of the black community” in his hometown.

Citing mostly anonymous sources, the paper added that “such feelings toward Mr. Walker have been present for decades” and are “flowering” ahead of Georgia’s U.S. Senate race, a highly competitive election that could determine which party controls the majority next year.

Benny “Chubby” Hodges, a 44-year-old truck driver who has lived in Wrightsville all his life, said, “From what I know about Herschel, he’s a good guy, man. He don’t see no, what they say, a racial divide of black and whites or whatever? That’s not Herschel, come on.”

Hodges, who is black, said he plans to vote for Walker.

He said, “Politics? I don’t know nothing about politics. I can’t lie. I just know about Herschel. He’s a awesome guy. … He never looked at me different, far as in where I come from, the streets, you know?”

Politico published a story in December similar to the one in the Times in which it called Walker’s neutral views on race “complicated.”

Walker, who often speaks about how he was overweight, had a speech impediment, and was bullied through middle school, transformed in the late seventies into an athletic fiend on Johnson County High School’s football and track teams. By 1980, he was a budding star and the number one college recruit in the country, the Times wrote at the time.

That same year, Walker chose not to become involved in turbulent protests against racism that lingered in the post-civil rights era in Wrightsville. Walker’s colorblind posture reportedly led some black students to deride him as “Uncle Tom.”

Both Politico and the Times drew what the latter described as a “dot-to-dot drawing” from that string of protests to today. The Times, in particular, claimed black residents’ lack of support for Walker, which mirrors their lack of support for Republican candidates across the country, is due not just to black voters historically overwhelmingly voting for Democrats but also to Walker’s decision to avoid his small town’s protests in high school.

In a wide-ranging interview with Breitbart News this month, Walker spoke about the Times story, lamenting that the outlet had attempted to stoke division.

“I think what’s sad about that, that reporter tried to bring in a lot of racism in that town, and, you know, years, years, years ago, there was a lot of racism in that town, but that town has come together,” Walker said.

Unearthing a decades-old period of turmoil and reviving tension that once existed between people based on their race only served to “make people angry,” Walker indicated.

“A lot of people in my hometown are really, really disturbed at that New York article,” Walker said. “I think what the New York Times guy did is what most politicians do is try to divide people and separate people and make people angry, and I think this guy did it in my little hometown because my little hometown is a good place with good people.”

Sue Hall, a retired teacher who graduated from Johnson County High School with Walker in 1980, found the Times story “very derogatory.” Half truths, she said, equal whole lies.

“Of course, there was some truth to some of the things of what happened in the ’70s, the racial issues,” Hall recalled as she sat on a bench outside the classic southern-style 1895 courthouse in the town square. “That was only part of it. … But as is happening right now, with this New York Times article, it’s people from the outside that come into our little small town, that stir up things and make things worse, and that’s the way that I remember it being at that time.”

Wrightsville, a downscale area with a mostly non-college educated population, is home to roughly 3,400 people, and Census data shows 1,534 are white and 1,820 are black.

“People get along here,” Hall said, noting black leaders in the community such as the elementary school principal, the superintendent, and the businessowner of the wing joint Felicia’s, one of just a handful of the restaurants spaced out around the sparse town.

In 1980, after Walker chose — by what he describes as a literal coin flip between Clemson and the University of Georgia — to play football for the Bulldogs, he went on to become third in the running for the Heisman Trophy as a rookie, the Heisman winner in 1982, a three-time SEC player of the year, an NFL player for a dozen years, a member of the U.S. Olympic bobsleigh team, a mixed martial arts professional, and a businessowner through H. Walker Enterprises.

Herschel Walker holds up the Heisman Trophy in front of the Johnson County courthouse in Wrightsville, Georgia, December 18, 1982. Several thousand fans, friends, and well wishers turned out to honor Walker at the appreciation day at his hometown. Walker’s mother Christine is in the center and his father Willis is standing at right. (AP Photo/Ric Feld)

Herschel Walker holds up the Heisman Trophy in front of the Johnson County courthouse in Wrightsville, Georgia, December 18, 1982. Several thousand fans, friends, and well wishers turned out to honor Walker at the appreciation day at his hometown. Walker’s mother Christine is in the center and his father Willis is standing at right. (AP Photo/Ric Feld)

After struggling with a dissociative identity disorder diagnosis, Walker authored a book in 2008 recounting aggressive outbursts he would have before seeking help for his mental health. He said he used to want to be a Marine, and he set off on a tour speaking to members of the military as a mental health advocate.

The Wounded Warrior Battalion of Camp Pendleton, California, hosted guest speaker Herschel Walker on November 3, 2017. (U.S. Marine Corps photo/Lance Cpl. Keely Dye)

The Wounded Warrior Battalion of Camp Pendleton, California, hosted guest speaker Herschel Walker on November 3, 2017. (U.S. Marine Corps photo/Lance Cpl. Keely Dye)

Now with his sights set on Congress, the accolade-laden Republican has at least some clear support from his hometown. If not already evident through the high school football field or street named after him, or the Herschel Walker signage in the local florist’s windows, or the testaments from those who have known him the longest, then perhaps through the primary turnout in May.

Walker was always expected to dominate in the primary, and he did, winning 68 percent of the vote statewide. But out of 159 counties, Johnson County had the strongest show of support; 91 percent of those who voted chose Walker.

A display on the wall where regular Rotary Club meetings are held at The Pizza Place in Wrightsville, Georgia. (Breitbart News)

A display on the wall where regular Rotary Club meetings are held at The Pizza Place in Wrightsville, Georgia. (Breitbart News)

Kreative Kreations, the local florist in Wrightsville, features Herschel Walker signs in its windows. (Breitbart News)

Kreative Kreations, the local florist in Wrightsville, features Herschel Walker signs in its windows. (Breitbart News)

Hall and others also spoke extensively about the contributions Walker has made to Wrightsville: Funding first graders’ field trips, donating bicycles, hosting football and cheerleading camps, contributing to the “Johnson County Class of 1980 Memorial Park” — a work-in-progress playground tucked near the entrance of a residential street — participating in the annual Fourth of July parade, providing financial support for things like high school class reunion events, small-dollar scholarships for the area schools, a Thanksgiving charity, and the remodeling of the high school field house.

Sumner said, “I’d be willing to bet there’s people that are recipients of good will from him that you’ll never know about, or hear about. He’s a private person. He’s not someone that’s ever treaded on fame or looked for credit for what he has done.”

Big thank you to @HerschelWalker for the youth cheer and football camp. Awesome experience!! pic.twitter.com/iX4Gmb6l0T

— JOCO Football (@jocofootball) July 11, 2015

In reference to Walker’s deeply rooted Christian faith, Sumner added, “I think he has really got a servant’s heart.”

Walker’s older sister Sharon, who has lived in Wrightsville all 63 years of her life, supports her brother’s Senate bid.

During a brief conversation on the phone, she said, “He will do whatever he can to help. It don’t matter what color you are, and I’m all for him running. I’m praying for him.”

Charles Sutton, who has owned a pizza place called The Pizza Place in Wrightsville for 20 years, said he plans to vote for Walker.

“If he walked in this door now, he would hug you, shake your hand,” Sutton said, standing near the entrance of his restaurant, another one of the few around town.

Being famous with small-town roots lends itself to expectations or even entitlement among some, Sutton explained.

“A lot of people give him a bad rap because they just felt like he should’ve spent more money here, but he has supported this community,” Sutton asserted, adding that “people just, they use that money issue I think for the wrong reasons.”

In the Senate race, Walker is up against another prominent black man, Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA), who has served as the longtime pastor of Atlanta’s historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr. once preached.

At a rally in Carrollton this month, Walker owned the campaign stump as he spoke to a crowd of supporters about Warnock, saying, “He’s gonna talk sweet to you. He’s gonna dress nice, but two years he’s been in office, and can you take six more of this here? You can’t take six more of this.”

Ashley Oliver / Breitbart News

Willy Chappell, a rally attendee who is black and from the Carrollton area, was asked by Breitbart News if media attacks on both Walker’s trials in his personal relationships and his views on race affect his support for Walker.

“It doesn’t at all because we know what happens in the media, and I’ve often heard that someone can tell a lie and it can get up and get dressed in the morning and go all around the world before truth can even get out of bed, so the point is you have to be able to separate fact from fiction,” Chappell said.

He added, “He comes from good stock, and if anybody’s able to do the job and do it like we need it to get done, we need somebody like Herschel.”