His new project about African samurai Yasuke will appear on Netflix this spring

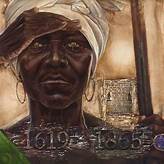

The protagonist of Netflix’s new anime series, Yasuke, is a true historical oddity: an African who entered 16th-century Japan with a Jesuit missionary and then became a samurai under Japan’s most powerful warlord. Legend has it that when they first met, the warlord, Oda Nobunaga, ordered Yasuke (pronounced YAS-kay) to strip and scrub his body, assuming that the foreigner had painted himself with black ink.

Yasuke’s creator, producer and director, LeSean Thomas, a native of South Bronx, New York, also made an improbable move to the Far East. His busy early career culminated in 2005-06 with codirecting several episodes in the first two seasons of The Boondocks, an animated television series based on Aaron McGruder’s groundbreaking comic strip.

By that time, Thomas, who was living in Los Angeles, recognized that the bulk of animation production was outsourced to South Korea and Japan. So he moved to South Korea in 2009 to immerse himself in the grunt work of the industry. “My thinking was that if I went to work in South Korea, that would put me above my animation production peers in the United States,” Thomas said during a recent Skype conversation.

A decade later, after Thomas moved to Tokyo, Netflix aired Cannon Busters, which he adapted from his own comic book series. But Yasuke, which debuts in the spring, is his highest-profile venture yet, with LaKeith Stanfield (Atlanta, Get Out, Sorry to Bother You) voicing the character of Yasuke and Flying Lotus composing the musical score.

Lotus, otherwise known as Steven Ellison, recalls being approached by a producer to join the project. “He said, ‘Yo, man, you want to work on an anime series for Netflix about a Black samurai?’ I was like, ‘Are you … kidding me?!’ ”

Thomas grew up in the John Adams Houses projects in the South Bronx. He’s the second-oldest of eight children who were raised primarily by their mother. “He started drawing because I was drawing,” said Thomas’ older brother, Kelby, who lives in Florida. Kelby moved on to other hobbies, but “Sean never stopped,” he said. “I wish we still had some of the comic books he made when he was in elementary school.”

With so many siblings competing for attention, Thomas said, he was content to spend long hours by himself. But at school, his penchant for drawing during class got him into trouble. “I couldn’t relate to my teachers,” he said. “They were all white. They were like police or bank owners. They stood there and all they were interested in was if you knew Columbus discovered America. They didn’t look like me. They didn’t talk the way I talked.”

Netflix

Looking back, he realized that much of his learning was occurring outside the school’s walls. “When I was 8 or 9, it was 1983 and 1984 in New York City,” he said. “You had Reaganomics, the crack epidemic, the war on drugs. There was the birth of hip-hop culture and Basquiat – all these great movements when New York was broke.”

Rather than fight her son’s artistic inclinations, Thomas’ mother enrolled him in the arts program at Julia Richman High School, the site of early reform efforts in the city’s public schools. When he graduated, “I knew I wanted to be an artist, it was just trying to figure out how I was going to get there,” Thomas said. He wanted to be a comic book artist, but the competition in New York for jobs at Marvel and DC was stiff. “You’re not special in New York,” he said. “Everyone has to hustle, and I learned other skills.”

He took a series of drawing jobs, including designing kid-themed backpacks and making a cartoon for a web startup called Urban Box Office. That led to an assistant gig at a New York animation studio that produced comedy shorts for Saturday Night Live and the animated bits on the television show Lizzie McGuire.

Meanwhile, Thomas’ drawing style was changing. In high school, “my drawing was super-realistic, in the style of DC and Marvel comics,” he said. “But when I got the job designing backpacks featuring SpongeBob and Disney characters, I had to simplify my drawing to match the Disney cartoon style.”

In his spare time, Thomas was absorbing and emulating Japanese animation, which set him apart from most of his comic-drawing friends. “More people were into comics because of accessibility,” Thomas said. “They didn’t sell animation in the bodegas in the ’hood.” But Thomas found VHS copies of anime series for sale in Chinatown, and he devoured movies such as Akira and Ghost in the Shell.

Netflix

Thomas’ mother died in 2000. “That dramatically affected my mental state,” he said. A year later came 9/11. Thomas had spent his entire life in New York, but he was ready for a move, and in 2002 he joined a friend in Greensboro, North Carolina, working remotely for a Canadian comic book company. “It was a massive culture shock being in the South,” Thomas said. “But by then I was such a recluse, I could spend 15 hours a day drawing.”

In North Carolina, Thomas met another talented illustrator, Carl Jones, who would soon move to Los Angeles and work with McGruder on The Boondocks. Jones made an introduction, and McGruder hired Thomas as the character supervisor for season one. “Working on that show changed my perspective,” Thomas said. “I never saw a Black man command a room like Aaron did and have such a strong point of view. The first time I was like, ‘Yo, you’re not supposed to talk to white people this way.’ And he was like, ‘F— that.’ ”

Thomas worked on The Boondocks for two seasons, but when the third season was delayed, he left for Cartoon Network and later worked for Warner Bros. But he was itching to do his own work and was disillusioned with the traditional route. “If you wanted to sell a show, you pitched your idea,” Thomas explained. “A studio would buy it or not without seeing any animation, and a lot of the time, even if a studio bought it, the show would stay in development limbo for years.”

Thomas thought a better way would be to produce a high-quality trailer and pitch the polished product. To do that economically, he’d have to go to South Korea. “My thinking was sort of like [Harlem drug lord] Frank Lucas from the movie American Gangster,” he said. “Go where the source is and get your own before it gets stepped on.”

He got hired at JM Animation, a Seoul, South Korea-based studio – a career step backward in some ways. He was earning less money than he would in the United States and working longer hours. But Thomas was mastering every aspect of the animation process and would go on to work for other studios in Seoul and on international projects as a freelancer. (He chronicled his experiences in South Korea in a video series called Seoul Sessions.)

Netflix

Thomas was lured back to Los Angeles in 2012 to direct the animated series Black Dynamite, his friend Jones’ winking homage to blaxploitation cinema. Meanwhile, financed in part with a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign, he was finishing the pilot for Cannon Busters, a fantasy-action romp through a sci-fi Wild West featuring multiple Black characters.

The project caught the attention of Jerome Mazandarani, managing director for Manga UK/Funimation, at an industry event in California. “LeSean had a great pedigree and he already had a great Japanese studio, Satelight, involved,” he said. “So as a marketing guy, it had all the ingredients I knew that would enable me to sell it internationally.”

Mazandarani, who served as an executive producer on Cannon Busters, also saw the appeal of introducing diverse characters into the anime market to better reflect the diversity of the international fan base. “The thing that really stuck with me – and I’m a white dude – is what [LeSean] said to me: ‘Look, when you’re a young Black person or brown person or Asian person and you like watching cartoons and comics and fairy tales, you imagine yourself as the knight in shining armor slaying the dragon. You imagine yourself as the princess in the high castle, or the space ranger, or Han Solo.’ That made me want to do the show.”

With additional investment from British and Taiwanese investors, Netflix greenlit Cannon Busters in the summer of 2017 and Thomas moved to Tokyo that fall to dedicate himself to the project.

Netflix was expanding its commitment to anime and approached Thomas about future projects. He mentioned a series based on Yasuke, and Netflix wanted it to be his next project. “LaKeith was on board and they asked me what I thought of Flying Lotus,” Thomas said. “What?! I have all of his albums. LaKeith and FlyLo are this generation’s maestros in terms of African American artistry as far as I’m concerned.”

Not much is known about Yasuke, who likely was born in Mozambique but fades from historical literature after the death of his warlord. Nobunaga, who unified much of feudal Japan, was betrayed by a top deputy and forced to commit seppuku, ritual suicide. “Never in a million years would I have thought that there was this African samurai for the most famous warlord in Japanese history and no one has made a movie about it,” Thomas said.

In fact, someone else was trying. Around the same time, Hollywood executives were thinking about making a live-action biopic, and Chadwick Boseman, fresh off playing Black Panther in Avengers: Endgame, had signed on. “The legend of Yasuke is one of history’s best kept secrets, the only person of non-Asian origin to become a samurai,” Boseman told Deadline. “That’s not just an action movie, that’s a cultural event, an exchange, and I am excited to be part of it.” Sadly, Boseman died of cancer last year.

Thomas’ anime take on the Yasuke story is not a traditional biopic. While there are flashbacks, the story largely takes place in an imagined aftermath of Nobunaga’s betrayal and includes supernatural elements. That narrative freedom appealed to Ellison. “That’s part of the reason they brought me on board, to throw some trippy fireballs at them,” he said. “I’ve been able to contribute ideas and come up with characters and obviously do the music. It’s been a great collaboration.” Stanfield, meanwhile, helped shape Yasuke’s traumatic backstory, Thomas said.

Ellison said he was impressed with how well Thomas managed the international team. And while anime is less dependent on in-person interaction than live-action, the pandemic still posed logistical challenges. “LeSean was really good at staying level and staying balanced,” Ellison said. “When you have such a big role, with so many hands involved and so much needing your attention, it can get overwhelming. But he handled it very gracefully.”

Thomas said he’s interested in how his show will be received internationally, but particularly in Japan, where he plans to remain for the foreseeable future. “More than anything, the story of Yasuke is Japanese history,” he said. “Hopefully, this show starts a dialogue about cultural cross-pollination.”

And it’s not a major spoiler to note that at the end of the series Yasuke remains alive, a masterless samurai prepared for whichever adventures Thomas can dream up next. “We’re crafting this show to have multiple seasons,” he said.