Seven-year-old Viola Fletcher was awakened by her parents 100 years ago today and told they had to leave home.

Angry, gun-toting white mobs had set out under the cover of nightfall in her hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, to kill Black people and destroy Black America’s economic mecca.

Now 107, Fletcher recalls the night that forever changed Tulsa.

“People running and screaming. And noise from the air like an airplane. And — just so many things was disturbing, you know. And fires burning, and smelling smoke,” Fletcher told NBC News. “And then we could hear someone going through the neighborhood … that everybody should leave town, that they were killing all the Black people. So, you know, that was frighten ing.”

ing.”

By 1921, Greenwood was a cultural inspiration representing Black prosperity, economic achievement and progress.

Tailors, shoeshiners, Black-owned groceries, theaters, jitneys, accountant and doctor offices, dance halls, schools, a library and post office defined the thriving, segregated 35-square-block district that Booker T. Washington was credited with dubbing “The Negro Wall Street of America.”

Sometime later, the name morphed into “Black Wall Street.”

But within 16 hours, the self-sufficient Greenwood was turned into rubble in what became known as the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Officially, 37 people were killed, according to records.

However, many Black Tulsans and historians estimate that up to 300 lives were lost, with the missing bodies being dumped in the nearby Arkansas River.

Three survivors from that infamous night are alive.

Fletcher and her brother, Hughes Van Ellis, who was an infant at the time, are two of them.

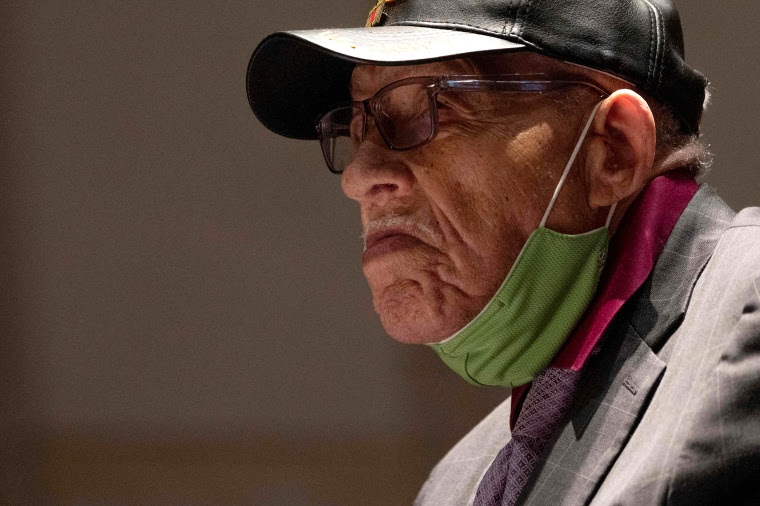

“It sticks in my mind. I wake up about four times a night, you know. Some nights, I’ll stay woke, say, 30, 40 minutes till I can lay back down,” Van Ellis told NBC News. “I can’t sleep at night. I have to have light. I love light. When I got old enough to marry and raise a family, that’s when, yeah, dawned on me so much.”

Hughes Van Ellis, a Tulsa Race Massacre survivor and World War II veteran, testifies before the Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Subcommittee hearing on “Continuing Injustice: The Centennial of the Tulsa-Greenwood Race Massacre” on Capitol Hill in on May 19, 2021.Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images

Witnessing Blacks fleeing, being murdered and seeing homes looted has been hard to outlive.

“It just kind of stays with you. It’s something you don’t forget; you think about that all the time,” Fletcher said. “Every evening, you know, I kind of have a feeling it’s time to run and no telling what might happen. But I’m sure it won’t happen again.”

She added: “People was getting killed and seemed like they were breaking in people’s homes and taking … some of their valuables. But just ransacking the neighborhood, you know, damaging most everything that the Black people had.”

About 9,000 Blacks lived in and around Greenwood Avenue, just northeast of downtown Tulsa, before the massacre.

At least 1,250 Black homes were destroyed in addition to other commercial businesses.

Conservative property damage estimates were $1.5 million to $2 million, which equates to more than $25 million today, said Hannibal B. Johnson, a Tulsan and a Harvard Law School graduate and historian who has written four books on the Greenwood Avenue district.

The massacre was caused by numerous factors, including racism, land lust by railroads and industrialists for which the community sat, jealousy over the success of Black people, expansion of the Ku Klux Klan and the former Tulsa Tribune, he said.

The afternoon newspaper wrote a story with the headline, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

Crowds of people watching the fires on June 1, 1921 in Tulsa, Okla., looking from Cincinnati Ave. from 2nd St. to Detroit Ave.Department of Special Collections, McFarlin Library, The University of Tulsa

“It’s no longer a Black mecca, but we don’t live in that type of society anymore. It’s a different integrated community. The ownership of the land has changed; the community composition has changed dramatically. It’s in the midst of a renaissance,” Johnson said. “The history doesn’t change though, and we can understand and leverage that history.”

A reparations lawsuit was filed last year arguing that the state of Oklahoma and Tulsa are responsible for the massacre, according to Tulsa County District Court records.

Plaintiffs include the last survivor, Lessie Benningfield Randle; the Tulsa African Ancestral Society; and others.

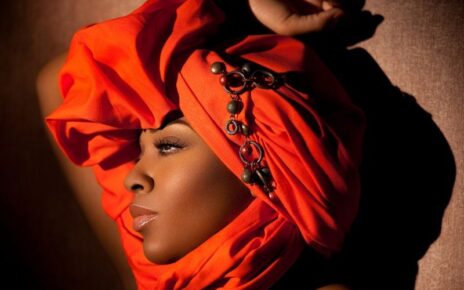

Earlier this month, Fletcher traveled to Washington for the first time to address Capitol Hill lawmakers about the suffering, pain and loss for herself, survivors and victims.

She said her schooling never passed the fourth grade and that she struggles to support herself.

“I’m a survivor of the Tulsa Race Massacre. I’m here seeking justice, and I’m asking my country to acknowledge what happened in Tulsa in 1921. The night of the massacre, I was awakened by my family, my parents and five siblings were there. I was told we had to leave and that was it,” Fletcher said. “We lost everything that day. Our homes, our newspaper (The Tulsa Star), our theaters, our lives. Greenwood represented all the best of what was possible for Black people in America. This Congress must recognize us and our history.”

She reiterated the emotional scar the riots have left on her.

“I will never forget the violence of the white mob when we left our home. I still see Black men being shot and bodies in the street. I still see Black businesses being burned. I hear the screams. Our country may forget this history, but I cannot. I will not,” Fletcher said. “I have never made much money in my country. The state (and) city took a lot from me. Most of my life I was a domestic server serving white families. To this day, I can barely afford my everyday needs.”

Van Ellis, who accompanied his sister on the trip, blamed the riots on the low wages he made as a young man.

“Please do not let me leave this Earth without justice,” Van Ellis told Congress.